Legacy

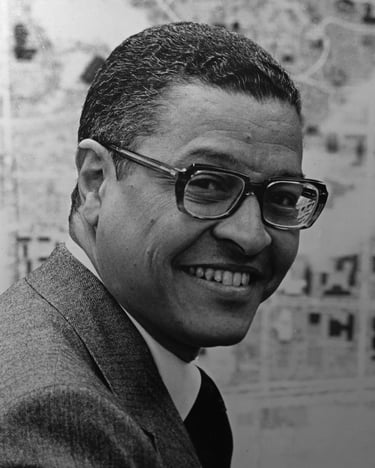

Clifton R. Wharton Jr.: A trailblazer in higher education and beyond

“Michigan State University has always embraced values and commitments to what a university is really created to be. With its profound generosity of spirit, MSU is open-minded and open-hearted while pursuing intellectual excellence. That is the transcendent soul of Michigan State.”

—Dr. Clifton R. Wharton Jr.

In his eventful life and career, Clifton R. Wharton Jr. achieved many firsts. Those included becoming the first Black president of a major U.S. public research university — Michigan State University. He was a widely respected trailblazer across multiple fields spanning his career, from higher education to philanthropy to the corporate world, and he influenced generations of leaders.

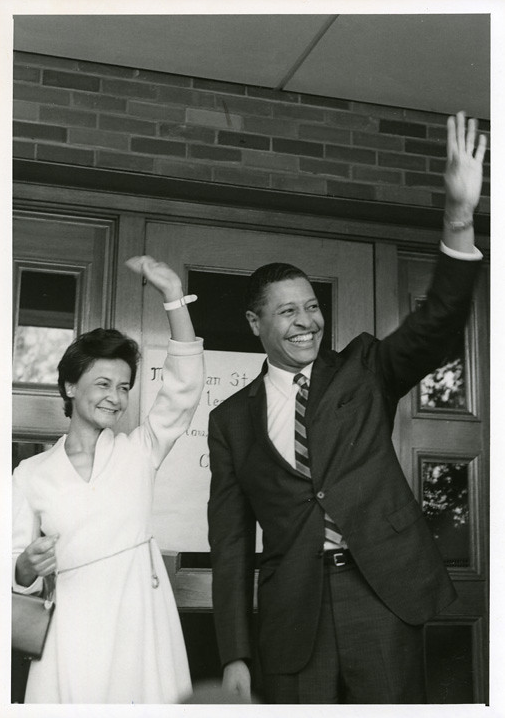

Wharton, who was president of MSU from 1970 to 1978, oversaw the building of MSU’s first superconducting cyclotron, the creation of the MSU Foundation and the launch of its first capital campaign. The capital campaign led to the construction of Michigan’s largest performing arts center, and in 1982, MSU’s Board of Trustees voted to name it the Clifton and Dolores Wharton Center for Performing Arts.

Wharton, who was president of MSU from 1970 to 1978, oversaw the building of MSU’s first superconducting cyclotron, the creation of the MSU Foundation and the launch of its first capital campaign. The capital campaign led to the construction of Michigan’s largest performing arts center, and in 1982, MSU’s Board of Trustees voted to name it the Clifton and Dolores Wharton Center for Performing Arts.

Among his colleagues, Wharton was respected for maintaining the quality of MSU’s academic programs despite budget constraints, as well as his commitment to educating the economically disadvantaged. While he led MSU, the number of Rhodes Scholars rose, and two new colleges opened: the College of Urban Development and the College of Osteopathic Medicine.

Wharton was 43 years old when he became president of MSU. As his career of “firsts” progressed, it often attracted news media attention. When he was named president of MSU, the New York Times took note.

His time in office coincided with the Vietnam War and student protests, but Wharton was committed to dialogue and engaging with students. He formed the Presidential Commission on Admissions and Student Body Composition, which included faculty, students and others to examine MSU's admission policies and recommend ways to broaden access, especially to disadvantaged students. Wharton approved new anti-discrimination policies and procedures and established an anti-discrimination judicial board.

“President Wharton’s steadfast commitment to creating a ‘pluralistic university,’ in which we solve the grand challenges of our time by opening our doors to accommodate students of more diverse backgrounds and needs, is an enduring legacy that is still seen today on our campus,” said MSU President Kevin M. Guskiewicz, Ph.D. “That welcoming atmosphere drew me to this campus. Each day, it’s a reminder of the impact of Clif’s service to MSU.

“My wife Amy and I are grateful for the Whartons’ warm embrace as we joined this incredible community. In my first meeting with him in April, he encouraged me to be bold in leading the university, and that we will do.”

During his tenure as president, Wharton demonstrated keen leadership skills and maintained a strong commitment to developing talent and bringing out the best in people. He was noted for his ability to spot rising talent and for the number of his associates who went on to lead other universities. Wharton created a Presidential Fellows Program, in which students and junior faculty members were assigned to work in MSU leadership offices.

“Clifton Wharton cared deeply about students and their welfare, and he sought to create new opportunities for them, such as the presidential fellowships,” said Teresa Sullivan, president emerita of the University of Virginia and a former MSU interim provost who, as a student here, was tapped to be a Presidential Fellow. “He was always open to new ideas and sought people’s opinions, and he understood the value of shared governance for universities. In a time of great turmoil for higher education, he was calm, reasoned and driven by his principles.”

Another Presidential Fellow, retired MSU sociology professor and Community Engagement Scholarship Lifetime Achievement awardee Carl S. Taylor, recalled how “Dr. Wharton impressed upon me the nucleus of my skills set. One must be always truthful with oneself, first and foremost. He expressed the necessity of being truthful with himself before anything else. During a meeting, I indicated my curiosity about leadership style. ‘Education,’ he said, ‘is key in leadership development.’”

James Spaniolo served as an assistant to Wharton from 1970 to 1972. He became dean of MSU’s College of Communication Arts and Sciences before his career took him to Texas, where he was president of the University of Texas at Arlington.

“For more than 50 years, Dr. Wharton was my leader, role model, mentor and dear friend. Working with and for him in the early years of his presidency at MSU changed my life and career,” Spaniolo said. “But for his inspiring example and encouragement, I likely would not have aspired to be a university president. Throughout his long, distinguished career, he left indelible legacies at the institutions he served and led. He was truly one of my heroes!”

Spaniolo assessed Wharton’s influence in a 2019 Spartan magazine article. “In selecting Dr. Wharton,” he said, “Michigan State demonstrated that it was able to look beyond its own heritage in bringing in someone who had a different set of experiences. And I think that it helped Michigan State extend itself and mature into a major university. What President Wharton brought was a whole new dimension, and he helped create a new reputation and perception of Michigan State University as not just a state university, but as an emerging national university.”

Wharton appointed Charles Webb the university’s first director of planned giving and executive director of the MSU Foundation, now the MSU Research Foundation. Webb went on to lead Spring Arbor University as president.

“A focus on striving for excellence and making MSU the preeminent AAU/land-grant university was the driving force for President Wharton,” Webb recalled. “A statesman who genuinely cared for all people, a person of integrity, a savvy listener and a skillful consensus-maker were some of President Wharton’s strongest traits.

“As a result,” Webb said, “MSU experienced significant change, developing new governance structures, strengthening academic programs, expanding research, creating cultural programming, developing a healthier and more pluralistic university and expanding MSU’s global reach.”

The Whartons and the arts at MSU

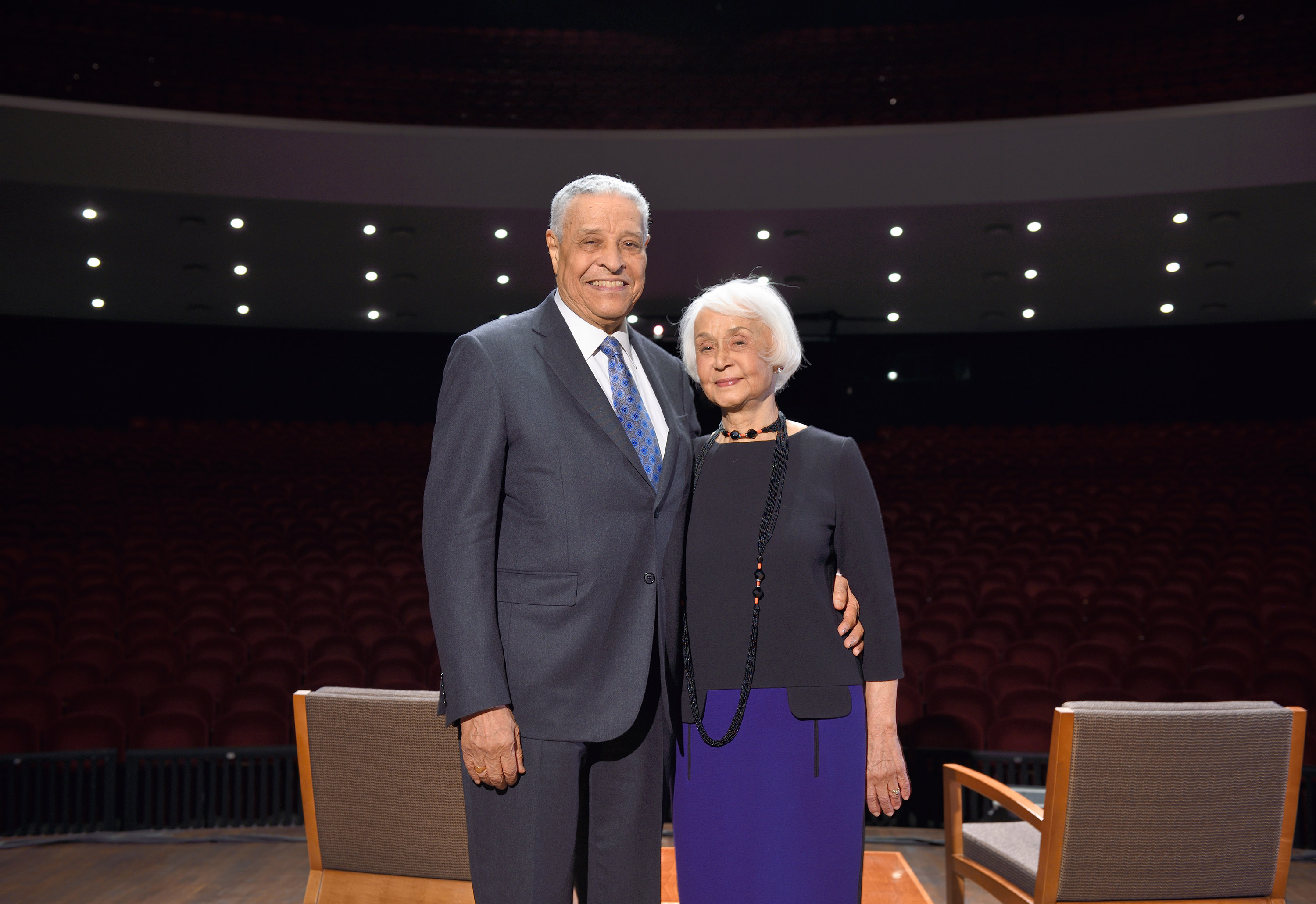

Wharton and his wife, Dolores, were avid supporters of the arts, admiring the arts’ ability to draw together people of all cultures and socioeconomic backgrounds.

Wharton “championed the integration of the performing arts into education, community life and public policy, fostering environments where creativity thrives and innovation flourishes,” recalled School of Hospitality Business Professor Bonnie Knutson, who has remained close to the Whartons. “Dr. Wharton’s legacy will always be a testament to the power of art to inspire, heal, and bring people together, leaving an indelible mark on the hearts and minds of all who have been touched by his vision.”

“Dr. Wharton believed that art and creativity had a vital role in the process of academic excellence,” added Eric Olmscheid, executive director of Wharton Center. “By celebrating creativity and creating meaningful and transformative performing arts experiences, Wharton Center embodies this belief. Through Wharton Center, Dr. Wharton’s legacy will live on.”

Dolores Wharton was a particularly influential arts advocate on campus, around Michigan and beyond. She elevated the visibility of MSU arts faculty members by featuring their artworks at Cowles House. Both were active in planning and fundraising for the performing arts center that would later bear their names.

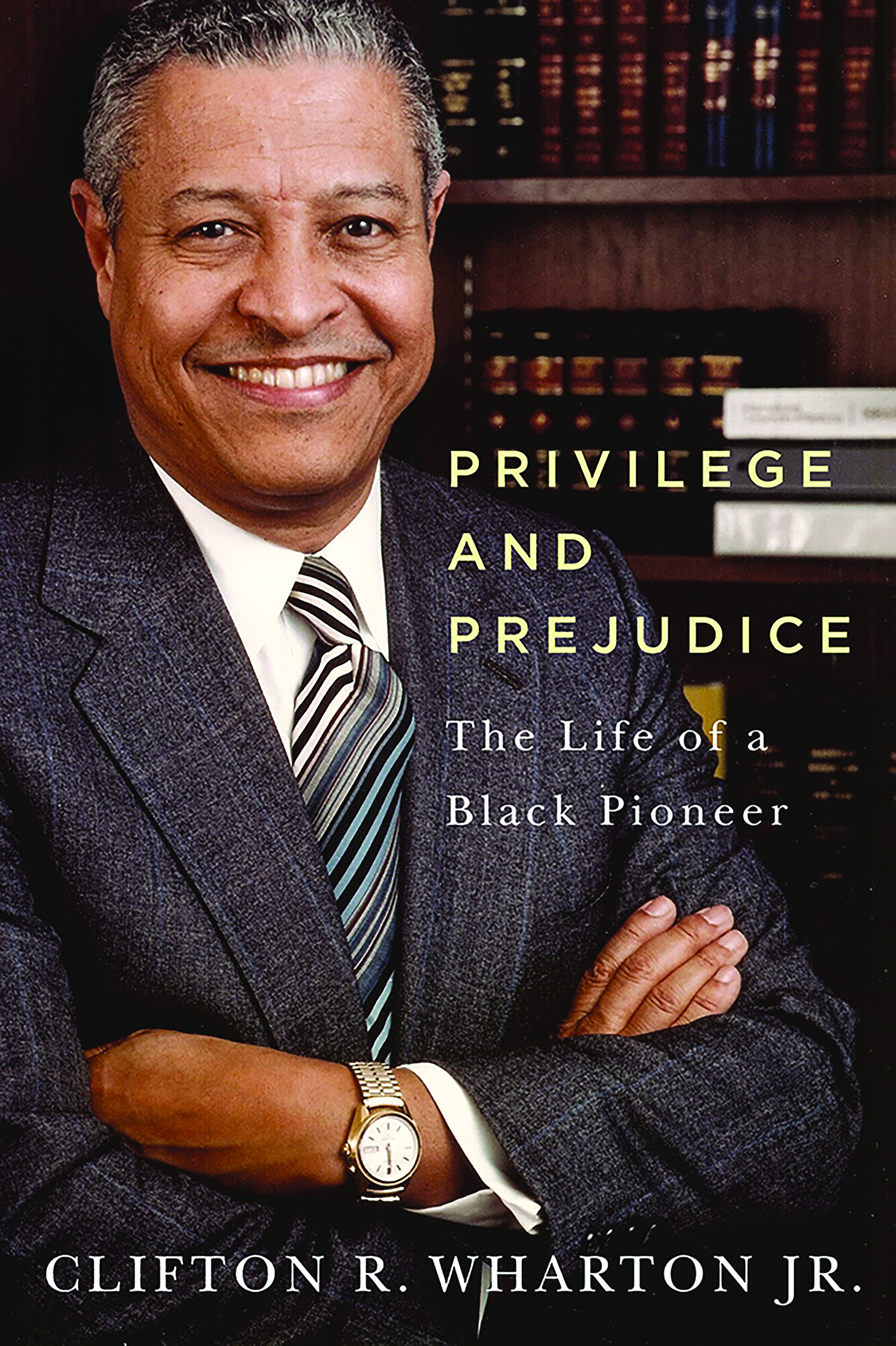

The Whartons returned to MSU in 2000 for a special convocation at Wharton Center. Clifton Wharton also returned for another Wharton Center event in 2015, following the release of his autobiography, “Privilege and Prejudice: The Life of a Black Pioneer,” published by MSU Press.

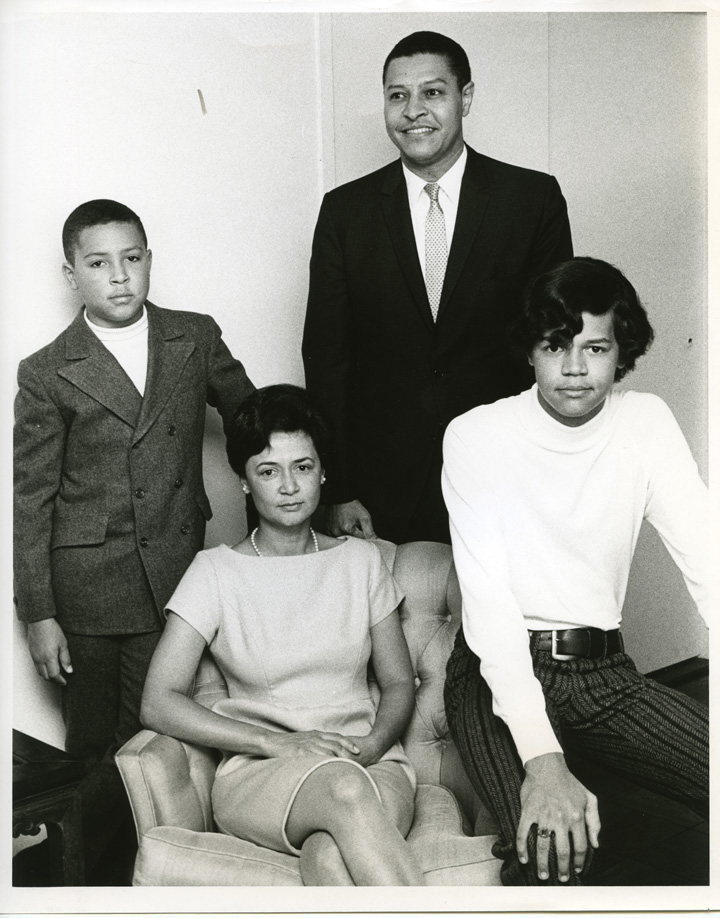

The Whartons had two children: Clifton III and Bruce. Bruce, their surviving son, fondly remembers his time with his parents at Michigan State University.

After MSU

After eight years as president of MSU, Wharton resigned to become chancellor of the State University of New York system. He was the first Black administrator to head the largest university system in the nation.

Wharton left higher education in 1982 to become chairperson of the Rockefeller Foundation. He joined the corporate world five years later as CEO of pension and financial services company TIAA-CREF, making him the first Black CEO of a Fortune 500 company.

In 1993, President Bill Clinton tapped Wharton to serve as deputy secretary of state, a position he held for a year. His post-retirement life included continued roles on corporate boards and serving as an “elder statesman” leading study groups, commissions and special panels. The organizations he served included the Asia Society, the New York Stock Exchange, and for the second time, the Knight Commission reviewing intercollegiate athletics.

Select honors and accomplishments

Wharton held appointments under six U.S. presidents. Among his many roles, he served as a member of the advisory panel on East Asia and the Pacific of the U.S. Department of State; the Presidential Task Force on Agriculture in Vietnam; Gov. Nelson A. Rockefeller’s Presidential Mission to Latin America; and President Jimmy Carter’s Commission on World Hunger.

Wharton also was appointed by Presidents Carter and Gerald R. Ford to chair the United States Agency for International Development’s Board for International Food and Agricultural Development. He was co-chairperson of the Commission on Security and Economic Assistance and was appointed by President George W. Bush to the Advisory Commission on Trade Policy and Negotiations.

In 1977, Wharton received the Joseph C. Wilson Award for achievement and promise in international affairs, and in 1983, he accepted the President’s Award on World Hunger. Among his many honorary degrees and other awards, Wharton received the Alumni Medal from the University of Chicago and the American Council on Education’s Distinguished Service Award for Life Achievement.

Early years

Wharton was born Sept. 13, 1926, in Boston, one of the family’s four children. His father, Clifton Wharton Sr., was the first Black U.S. foreign service officer to become an ambassador. Because of his father’s career, Wharton’s early education came while living in the Canary Islands, a Spanish possession off the northwestern coast of Africa, where, at an early age, he learned to speak Spanish and French.

Upon returning to the United States, Wharton lived with his grandmother to attend Boston Latin School. He graduated at 16 years old and enrolled at Harvard University, where he was the first Black student to work at the school’s radio station. He was also a founder of the National Student Association, an advocacy organization he credited with developing his leadership skills and familiarizing him with civil rights and other national issues.

After earning his bachelor’s degree in history from Harvard, Wharton became the first Black student admitted to the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies and the first to earn a master’s degree in international affairs there. He later earned another master’s degree and a doctorate in economics from the University of Chicago.

He was hired by Nelson Rockefeller’s American International Association for Economic Development, where his work took him to Latin America. He moved to the Rockefeller-associated Agricultural Development Council and worked in Southeast Asia, including teaching economics at the University of Malaysia. His early work for the Council took him on a tour of U.S. universities to assess their training of Asian graduate students in agricultural economics. Among the 15 he visited was Michigan State University.